An estimated 62 million girls globally are out of school, half of whom are adolescents. The highest number of adolescent girls out of school are sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. We have identified several causes of the widening gender gap at this time:

-

Health related needs – as girls hit puberty and transition to secondary school, they have different mental health and sexual reproductive health and rights (SRHR) needs, alongside heightened physical safety and pregnancy risks.

-

Gender roles and norms become more fixed and influential during adolescence; attitudes towards what girls can and should do impact on their learning, aspirations and transition to work.

-

Cumulative impact of setbacks – specific gendered challenges make it easier for girls to fall behind or drop out, especially if foundational learning is not in place.

-

Supply side barriers become more problematic at secondary level: increased distance, cost, time needed to study, subject specialisation, shortage of female teachers, selective entry and the impact of gender stereotyping in schools becomes even more pronounced.

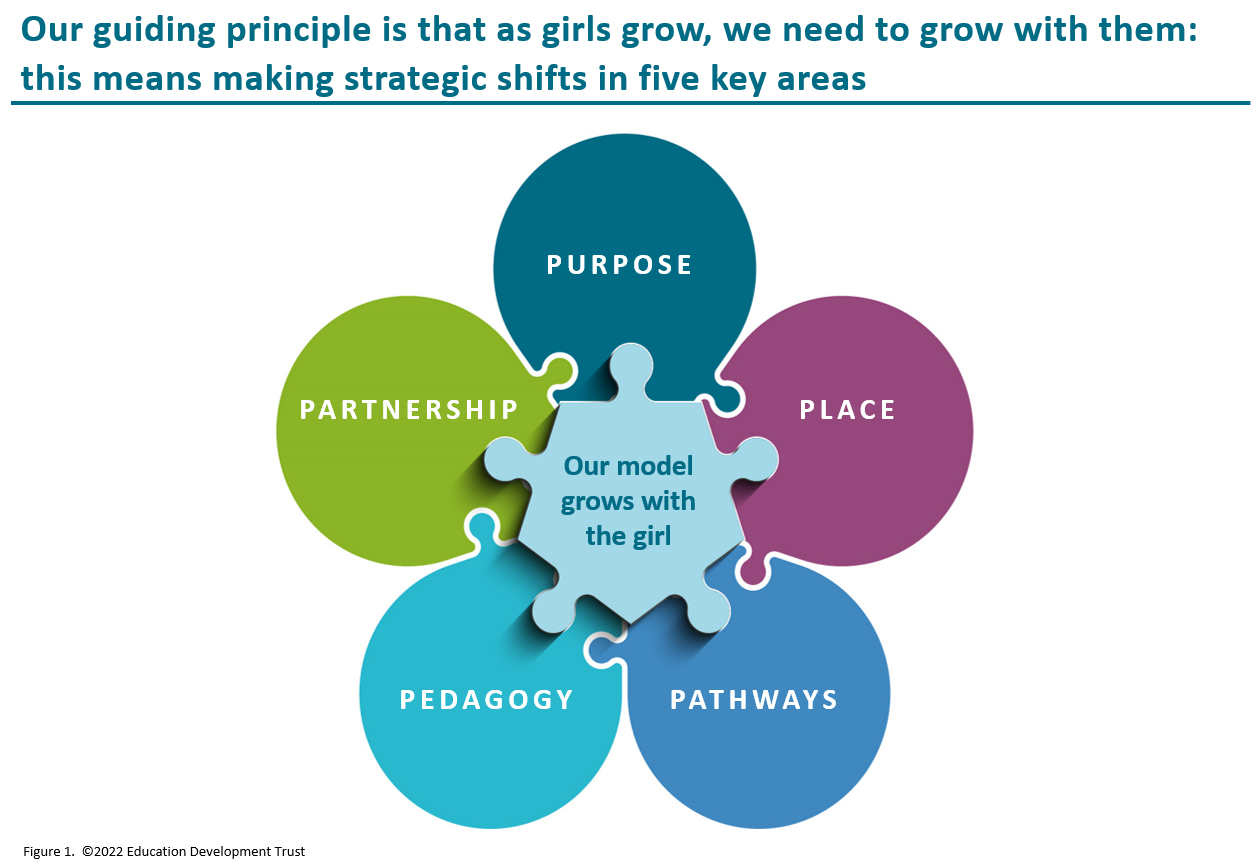

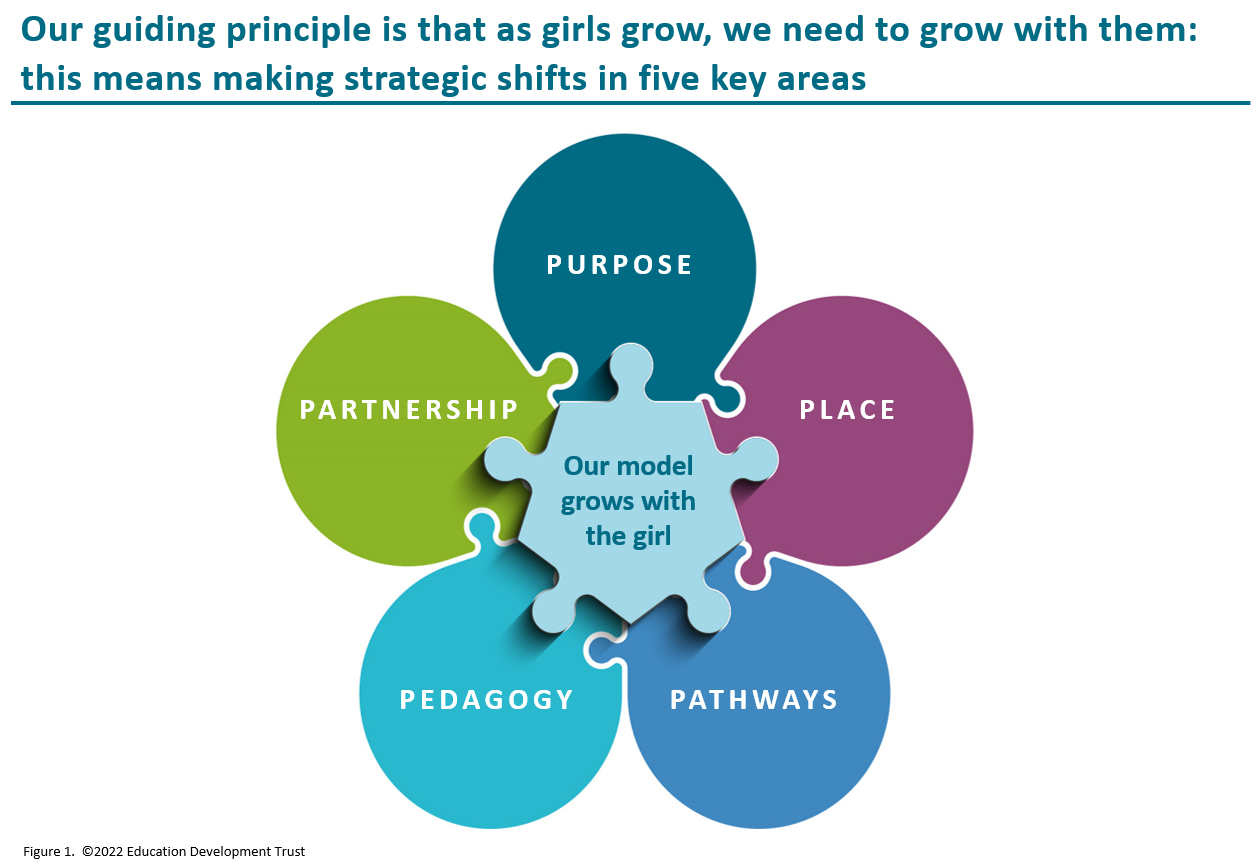

Our UK-funded adolescent girls project in Kenya, Wasichana Wetu Wafaulu (WWW), meaning ‘let our girls succeed’ is running in eight counties – six in arid and semi-arid lands and two in urban slums. By 2023, the project aims to support 72,000 girls in primary school to complete their current phase of education, achieve improved outcomes and successfully transition to the next phase of their education. At this critical point in a girl’s life, we focus on their changing needs and challenges ahead. Our approach is systemic, contextualised and rooted in good pedagogy and effective engagement beyond the school. It involves strategic shifts in five key areas:

1. Purpose

At adolescence, we approach education with a broader vision for how it equips girls to improve their life chances and we build multi-sector coalitions at system level to drive better outcomes. As such, the purpose of school widens beyond the provision foundational learning to teach girls life and livelihood skills and our curriculum encompasses SRHR lessons, financial literacy and psychosocial wellbeing to prepare students for life beyond the classroom.

To develop an effective and relevant curriculum (and accompanying teacher training), we combined our own global evidence with partners’ deep understanding of specific local needs. We also collaborated with the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development and continue to partner with Kesho Kenya, Ananda Marga Universal Relief Team and Concern Worldwide to co-design and implement responsive interventions across the eight programme counties.

Our WWW project ensures families and communities understand that education is a high returns investment for adolescent girls. Using sensitisation and reflection exercises, parents and community members, including community elders, are engaged with girls’ education and better understand its myriad and lasting benefits. This includes the importance of re-enrolment for girls who are pregnant, married or with childcare needs. The father of one girl, who overcame great odds to attend to secondary school last year, is now the girl’s education champion for his village. He said,

'We have been having community conversations especially on having our girls complete primary and go to secondary school like my daughter. I’m happy that soon we will have more girls in secondary school.'

Before his daughter transitioned, her secondary school had just one other female student. However, as a result changing attitudes, transition to secondary school on the programme is now at 97%. Renewed focus on the purpose of girls’ education has enabled parents and communities to encourage large numbers – up to 60% – of out-of-school girls to return to school.

2. Place

By secondary school, the place where learning happens becomes much more varied and adaptable compared to primary level. Longer distances to school, increased independence, and the need to study beyond school hours means learning shifts from classroom-only to home and community spaces and alternative providers of catch-up and/or skills training. Girls on the WWW project are supported through this change – formal classroom lessons are complemented by the opportunity to learn in multiple co-curricular and cultural activities, low-tech digital spaces, girls’ social forums and afterschool clubs. We have also awarded travel grants to 1,731 girls who face long distances to boarding schools and have links with local transport service providers to ensure girls get to school safely. We also encourage girls to walk in groups for safety.

Children’s clubs are a key means of facilitating additional learning – we provide mentorship, curriculum materials and training to the ‘club champions’ (learners and teachers) who then facilitate the club activities. One Grade 8 pupil from Kwale county said,

‘The session was interesting because I want to perform well in school. Usually when we are together as girls, we do not engage with academics, especially during our free time. I have learned the importance of time management and healthy relationships and how they contribute to my performance. After the training, we started remedial learning with the mentors, and they supported us in grammar, spellings and tips on composition writing.’

Older girls also organise mentorship programmes during the school breaks. One mentee explained how sensitive and constructive mentorship boosted her confidence and ability to set goals:

‘At first, I did not even have the courage to discuss my grades as my performance was very poor. Zawadi helped me come up with a timetable and linked me up to a teacher who supports me academically. Now, my performance has greatly improved.’

During the Covid-19 school closures, the project initiated community-based learning whereby girls were organised into peer groups for academic learning and mentorship, with support from local teachers in the community. Our research showed that the reading camps, combined with paper-based learning resources, had the greatest impact on learning – average scores for girls were 8.3% higher for reading and 17.6% higher for mathematics compared to girls who had not accessed either.

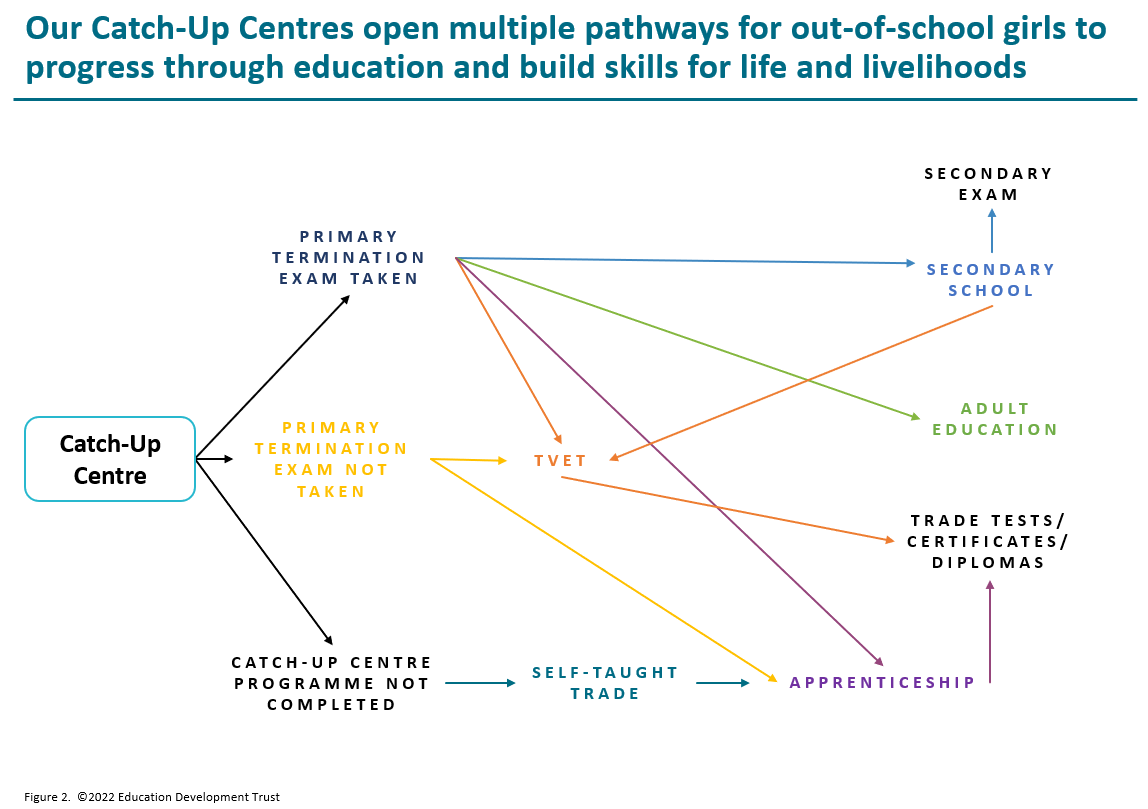

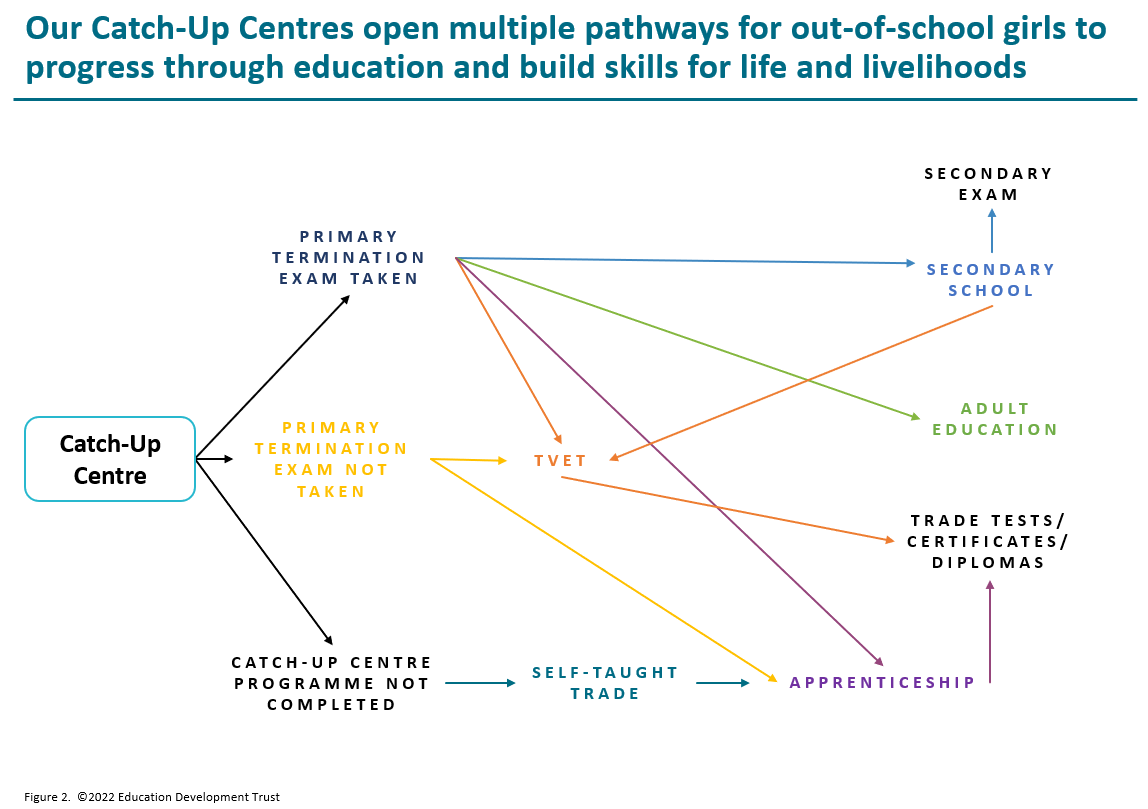

3. Pathways

Just as we reimagine the places where girls can learn at adolescence, we likewise expand the possible transition pathways for girls at this critical juncture (see figure 2 below). Faced with changing and additional barriers to learning, we support a more diverse range of ways for girls to reach their potential. This includes accelerated catch-up pathways for girls who have fallen behind, formal and informal tailored pathways for out-of-school girls, and progression pathways to vocational training.

Under WWW, we effectively engage girls who are out of school and facing barriers to re-entry through our Catch-Up Centres with community-led identification of the children most in need of support. Hosted in schools out-of-hours with wrap-around support to meet the needs of the girls, such as childcare, learners take an intensive Accelerated Education Programme that gives them a route back to formal education. Our Catch-Up Centres, which are embedded within the school system for long-term sustainability, have so far reached 885 girls, with 649 girls completing the programme and transitioning back to mainstream programmes or alternative pathways.

A popular alternative pathway, TVET – an accredited vocational training course, has been taken by 731 girls so far, while another 151 girls joined informal apprenticeship programmes. One girl from Samburu East, who signed up to TVET after finishing primary school, finished her course in electrical installations in March 2021 and is now the first female electrician in her town – with clear goals for her career. She said,

‘I want to become the best electrical technician. People in Wamba are not used to seeing women making electrical installations and when they see me they are amazed! I want to open a shop where I will sell electrical appliances and also install them for my customers for a fee.’

Meanwhile, a girl from Kilifi County explained how important it was to have another pathway open to her after school:

‘When I dropped out of secondary school, I did not know what to do. Luckily, the WWW team helped me to take a course on dressmaking. Now I have finished and started my business which is doing very well. In the next two years, I expect my business to have expanded so I can employ staff to help me.’

4. Pedagogy

At adolescence, we extend our model of good quality pedagogy for learning and equity to focus on specific subjects and curriculum areas relevant to gender equity. By focusing on STEM subjects for career transitions as well as SRHR education, the project addresses persistent gender inequalities in these areas. For example, after introducing designated ‘STEM hours’ to improve performance in science and maths and providing printed information on STEM courses available at universities, St Teresa’s School reported increased numbers of girls enrolling in STEM subjects.

WWW also prioritises teacher training and mentoring to raise consciousness of gender issues and enable gender-responsive lessons to directly benefit girls in their learning. We map gender-barriers in teaching and learning across subjects, and the data is used to deliver informed and contextualised trainings for teachers which include information on the social constructs and gendered-attitudes which hold girls back from learning. This is reinforced through classroom observation and the facilitation of teacher communities of practice – forums for teachers to connect across schools and districts and discuss strategies to counter negative stereotypes, build girls’ aspirations and support their out-of-school learning.

5. Partnerships

To meet the changing needs of adolescents, we engage more robustly and with a greater mix of people and professionals involved in supporting girls to access school and achieve. This includes working more closely with stakeholders at home, at school, in the community, at county level and with businesses – as well as adapting our approach to working with the girls themselves.

At home, we provide counselling to parents, guardians and elder siblings to support effective decisions on girls’ education. At the community level, we engage with local chiefs and community elders to drive enrolment, sustain attendance and challenge cultural barriers. We also use community conversations to identify ‘services’ which could support girls, such as joining up with relevant government social protection schemes and putting in place home visits.

At the county level, we engage the ministry of education around the implementation of gender policies, capacity building for teachers and curriculum support and we work with the Teachers Service Commission to support teacher recruitment and training. We also connect with businesses, building sustainable links with role models for girls. This also supports with breaking down stereotypes and aspiration-building for girls. Meanwhile, to address the increased safeguarding risks to girls at adolescence, we work with public, private and faith-based child protection institutions and police departments for effective response to child protection cases.

The project has also forged unusual partnerships with men who have not traditionally supported girls’ education, including with motorbike taxi riders in Kilifi and Tana River counties and Samburu morans (Massai warriors). The motorcyclists have been enlisted as ambassadors for girls’ education and one group of morans from Naisunyai recently sold several goats to cover the tuition fees of a girl attending technical training college in the village.

Finally, we believe in the importance of increasing engagement with adolescent girls and boys themselves, seeing them as changemakers for gender transformation. Through children’s clubs, girls are taught to be advocates for themselves, to understand education as a right, and how to recognise and navigate complex local dynamics and gender discrimination. We engage boys, too, by developing a gender-responsive pedagogy for teachers and integrating an understanding of gender the curriculum and extra-curricular activities. This encourages boys to reflect upon and challenge gender discriminatory norms and become advocates of girls’ education in their homes and at school.

Recommendations for an effective adolescent girls’ education project

The ‘Five Ps’ approach demonstrates the need for a dynamic and adaptive model to adolescent girls’ education. Below are four things we consider absolutely critical to the success of a new adolescent girls’ education project.

1. Partnership and collaboration – build knowledge and capacity on gender management among stakeholders; include parents and caregivers for effective home support; and build the capacity of school management and teachers to address the gender challenges.

2. Support school level implementation of the re-entry policy for the young mothers and ensure an accelerated curriculum is in place and effectively delivered to learners.

3. Ensure the project works progressively and holistically to build girls’ resilience and skills for the world beyond school and future careers. This should include a focus on:

-

Knowledge assets – enable quality, gender responsive teaching with emphasis on STEM subjects and digital literacy;

-

Financial assets – develop girls’ capacity to manage financial resources, explore early ventures into entrepreneurship, and build a culture of saving and investment;

-

Social assets – provide life skills training, mentorship and career guidance programmes;

-

Health and safety assets – deliver learning around sexual and reproductive health, hygiene management and responsiveness to emerging health and safeguarding issues.

4. Work on communal attitudes to education for girls to ensure barriers are broken down and the benefits of education clearly understood by all.